By Christopher H. Zakian

By Christopher H. Zakian

A certain stereotype of Christianity paints the church as puritanical and severe, an inhuman task master which begrudges the sound of laughter and the joys of life. In the 2000-year history of the religion, some Christians have indeed adopted such a worldview; but it is hardly characteristic of Christianity as a whole, and as far as the Armenian Christian tradition goes, nothing could be further from the truth. A single feast day in our liturgical calendar illustrates the connection between the life in Christ and the abiding concerns of human existence.

The “Blessing of the Grapes” is one of the most beloved ceremonies in the Armenian Church calendar. Most of us can recall people who would refuse to eat grapes until the fruit was “officially” sanctified by the local clergyman–a pious practice which dates back to an earlier era in the church's history, when daily life revolved around the growing seasons of an agricultural society.

Grapes do have a certain symbolic significance in Christianity (think of all the references which Jesus made to wine and to “the vine and the branch,” references which are still repeated in the Divine Liturgy). But for most people living during the early centuries of the church, the important thing about grapes was that they had to be harvested at a certain time of the year, and that, eaten as fruit or distilled into wine, they added something pleasing to life. In other words, for our ancestors, the grape season meant both labor and recreation. Through the grape blessing, the church gave it a further significance, one having to do with man's sacred obligations to God. Thus work, play and worship were all brought together in this ceremony.

The church was in effect saying to its followers: “What is important to you–the labor of your days, the joy of your festivals–is important to God as well. His church is not some otherworldly institution which is concerned only with what happens to souls after they die; to the contrary, the church is deeply interested in the living, and in being a part of all the seasons of life.”

Such a sentiment flies in the face of the secular stereotype of Christianity. But more than that, it is an example of what really sets our religion apart from other philosophies of life. The God of our fathers and mothers is not remote and aloof from human concerns. Indeed, He is profoundly moved by even the most ordinary experiences of life–our private troubles and our simple pleasures, the longings of our hearts and bodies, our gentle affection for family and friends. And God does not simply possess abstract knowledge of these matters; He has, if we may put it this way, first-hand experience in all of the human qualities, because He became a human being, lived among us, took on all our cares and concerns. Far from demeaning human life, Christianity in the fullness of its teaching lends to mere life a new meaning which it never had before: a spark of the divine. And this new meaning is embellished and played out through the offices and sacraments of the church.

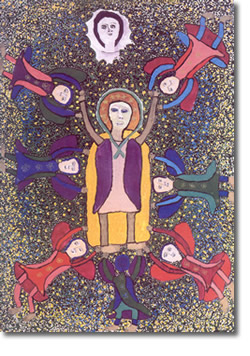

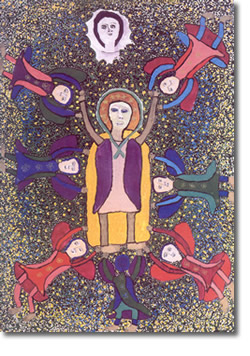

The occasion on which we celebrate the Blessing of the Grapes is a major feast day called the “Assumption of the Holy Mother-of-God,” and it, too, underscores a wonderful insight unique to Christianity. The story of the Assumption concerns St. Mary, the mother of Jesus Christ, and how having completed her life on earth, she was taken up in body and soul–“assumed”–into Heaven. This was a special courtesy, performed by Christ many years after His Ascension, as a loving tribute to the mother who bore and raised Him.

What is interesting is how this story, which at first glance seems to be about the death of a pious soul, is transformed into a beautiful illustration of a very special–and very familiar–kind of love. It is not uncommon in this world for grown children to want to share the fruits of their achievements with their parents, and to have their parents by their side. That sentiment is related to what Christ felt for His mother. Of course, this is comparing great things to small; but it is consistent with the Christian understanding that our common experiences of the world can offer us glimpses into the most cosmic truths.

One is reminded that before becoming man, God had no mother. The inhabitants of Heaven, the angels–beings of pure spirit–likewise have no mothers; only embodied, material beings do. Jesus touched on this general point during His earthly ministry when, in answer to a question about marriage in the Kingdom of God, He suggested that the ties binding us together on earth will not apply in Heaven (Mt 22:23-33). But the Assumption of Mary shows us another side of the story: even in Heaven, Christ's love for His mother endures. We might cautiously wonder whether Christ introduced something novel into Heaven, when He brought Mary to His side.

Once again, the simple, human love of child for parent is given that “spark of the divine,” by being reflected in God Himself. And at the same time, perhaps, Heaven is granted a poignancy, which it did not have before, by bearing witness to the human love of a son for his mother.

Through the combination on a single day of the Assumption and the Blessing of the Grapes, the Armenian Church reminds us that God understands and embraces the entirety of the human condition. The things that are important to us–our work, our recreation, our connection to other human beings–are important to Him as well; in some measure He is with us through all of these things, sharing our heartaches as well as our triumphs, our defeats as well as our victories. In becoming human, God reached out fully to us, His children. He did so not only to console us in our grief: He also wants to be with us in our happiest, most joyous moments. His presence in those times magnifies that joy, giving it power and meaning beyond itself.

Source: Website of the Diocese of the Armenian Church of America (Eastern), New York, USA

http://www.armenianchurch.net/worship/mary/assumption.html