The death of the former Afghan king marks an end to fantasies of a restoration of the ?golden era?.

The death of the former Afghan king marks an end to fantasies of a restoration of the ?golden era?.By Tanya Goudsouzian

MADRID

MADRID

The news reached me by way of a text message on my mobile: Zahir Shah is dead.

It came as no surprise. The 92-year-old former king of Afghanistan had been ailing for some time now, and many had cast doubt over his mental faculties in recent months. One report held that ?His Majesty? would awake some nights in his quarters at the (presidential) palace in Kabul and ask to be taken for a walk in Piazza Navona in Rome, where he had lived in exile following the coup d??tat led by his cousin Mohamed Daoud Khan in 1973.

The announcement of Zahir Shah?s death on 23 July, dealt a blow for those who harbored any fantasies of a restoration of ?the golden era? ? or so his reign has been dubbed by loyalists. But even for pragmatists who had accepted that the days of monarchy were for Afghanistan?s history books, Zahir Shah?s post-Taliban presence had come to symbolize hope for a prosperous and peaceful future, even as the instability in the country spiralled far beyond the control of the multi-national forces.

As a journalist who has covered Afghanistan passionately since 2001, and who strived to maintain her objectivity in reporting the events that transpired following the US carpet-bombing, which ousted the Taliban, my heart broke when I read the text message. Zahir Shah was dead. What now for the hapless people of Afghanistan?

My mind whirled back in time ? back to that city favored by so many exiled royals. It was August of 2001. Rome was sweltering, but around the world, the hottest topics were globalization and the Palestinian uprising. Afghanistan occasionally came up in the context of opium trade, mostly in UN reports. But the country was as far removed from popular Western consciousness as was the man who lost his throne, it is rumored, while having a therapeutic mudbath in Europe.

A friend of mine, a veteran Afghan mujahideen commander residing in Dubai, had organized an interview for me with Zahir Shah, after I had gotten wind of a scheme, spearheaded by the former king, to vanquish the ruling Taliban and restore peace. Perhaps I had a weakness for romantic (albeit, hopeless) causes, but within a month, I was boarding a plane to Rome.

I was instructed to meet the former king?s assistant at a hotel in the outskirts of the city. Moments later, we were joined by Zahir Shah?s youngest son, Prince Mirwais, who had just come from the airport, having assisted two Afghan nationals, whom the Italian authorities had mistaken for terrorists. (The pair were actually tribal elders from Herat province who had traveled to Rome to consult ?Baba Shah?, and not to protest violently against the globalization conference, which had been held in Italy a week back.) Following some chitchat with the prince, I was escorted to a burgundy Volvo, and off we went along a labyrinthine path to a modest villa.

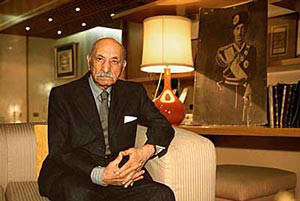

Zahir Shah emerged from the hallway, and extended a frail hand to greet me. He led me to the salon. A silk tapestry hung on the wall ? a gift from the late Shah of Iran, he explained. A servant brought in green tea and biscuits.

As we munched on the biscuits, Zahir Shah made some preliminary conversation in Dari (the Afghan dialect of Farsi) with his grandson Prince Mustafa serving as translator. He asked how I liked Dubai, saying he hoped to see it one day as he had heard amazing things were happening there.

During the interview, Zahir Shah spoke about his plan to hold a grand national assembly, or what he called a ?Loya Jirga?, in his country. He said he had sent emissaries to meet with all factions, including the ruling Taliban, and he dreamed of a day when they might all live together in harmony again. But without the support of North America and Europe, it seemed, the plan was nothing more than a mark of his good intentions.

Returning to Dubai, I learned that few people thought the former king mattered in the grand scheme of things. After all, Zahir Shah had lived a quiet life in exile in Italy throughout the years of political turmoil that followed his overthrow, prompting criticism that he had stood idly by while his country was shredded to pieces by warring factions.

Yet, the grand scheme of things would alter dramatically one month later. On 11 September, two airplanes sliced into the Twin Towers. Afghanistan began to generate headlines. Soon, Zahir Shah was the man of the hour, and his proposal to hold a ?Loya Jirga?, now endorsed by the Americans, was viewed as the key to peace. Germany played host to the negotiations, which saw the formation of a post-war interim government for Afghanistan, with the dubious title ?father of the nation? bestowed upon the former monarch, taking away any real political role from a man, who had steered the country for 40 years without bloodshed.

So it was that the man of the hour was gradually winnowed out of the scene by a bogus constitution penned under the supervision of self-interested foreign powers.

Zahir Shah might not have fit into the current set up in Afghanistan, but he stood to remind the Afghans of far better days. His absence from the scene may not shake up the government, but it will certainly be felt in the hearts and minds of many Afghans.

The article has originally appeared in the September 2007 issue of “Trends” magazine under the title “The King is Dead”.