By Anand Sagar

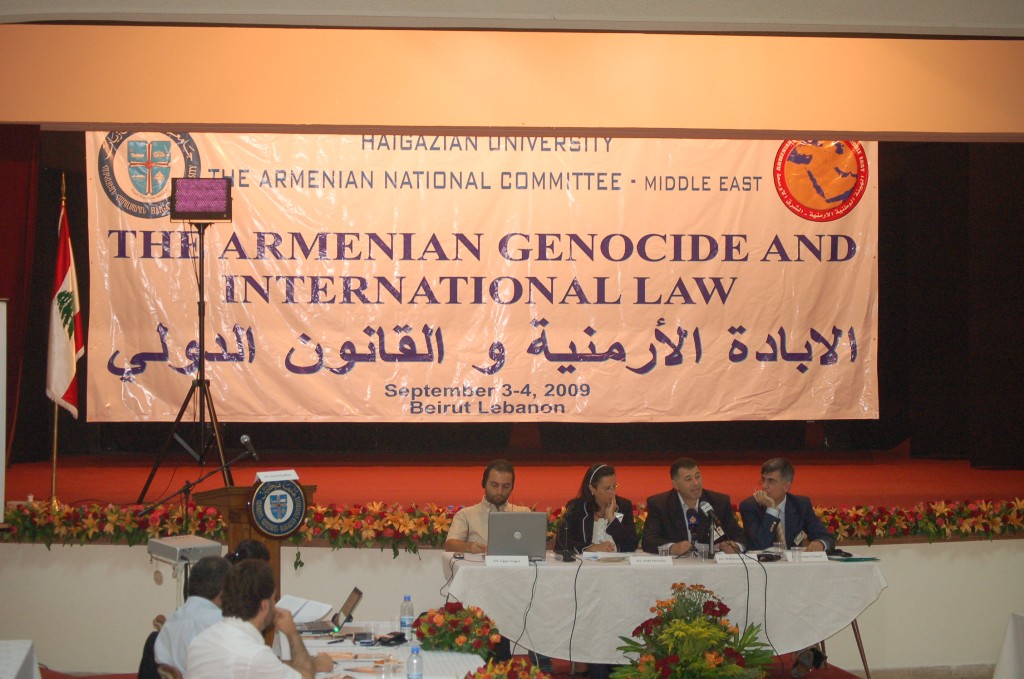

Nothing is more tragic than a lack of ?historical consciousness? as the Armenians know only too well and as was highlighted rather convincingly during a recent academic conference in Beirut – the first of its kind in the Middle East.

The main thrust of the conference, organised by the Armenian National Committee of the Middle East (ANCME) in collaboration with Beirut?s Haigazian University, was to ensure that the Armenian Genocide is not dismissed as a ?forgotten genocide?. And that, because an estimated 1.5 million Armenian citizens of the former Ottoman Empire (presently Turkey) had lost their lives in the ?Holocaust? – during and just after the World War I. And because, any tragedy of this nature and on this scale must never be reduced to a mere obscure footnote in history.

Also, as Vera Yacoubian, ANCME?s Executive Director pointed out, ?The reason why it is still relevant to ensure that the lessons of history are never forgotten is because in this era of globalisation, properly and adequately addressing the Armenian Genocide may likely reduce the chances of mass killings in the 21st century.? It?s an argument well made but not too widely acknowledged. Nevertheless, adds Vera, ?we strongly feel that it is the duty of the international community to resolve this issue and promote a fair solution through international law. That ought to be reason enough for expanding Hai Tad – the Armenian Cause.?

In fact, as was emphasised in a conference paper authored by Dr. Taner Akcam (and read out in absentia), the lack of historical consciousness in Turkish society implies that, ?without coming to terms with history, we cannot build a democratic future.?

It may be briefly recalled that Armenians were (during 1915-1918) subjected to deportation, expropriation, abduction, torture, massacre and starvation. These acts were committed under the cover of a news blackout on account of the war. The atrocities were renewed between 1920 and 1923. Akcam, a noted academic and an authority on the subject, argued that ?not merely not to forget, but actually to institutionalise remembering is essential for the process of democratisation,? and that this process would benefit both the modern Turkish society and the Armenian diaspora.

Also, he said, ?it is very evident that if we, the Turks, Kurds, Cherkess, and, in fact, all ethnic and religious collectives of Turkey do not sincerely confront our recent history, we will not be able to resolve the human rights issues. A dialogue with the Armenians is a key to the abolition of human rights issues and for the democratisation of Turkey. The survival of Armenia, freedom in the region, and the welfare of the Armenian community within Turkey itself are all linked.?

Many participants like Dr. Richard Hovannisian from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) and Prof. Roger W. Smith, Director of the Zoyran Institute?s Genocide and Human Rights University, argued quite convincingly that the Armenian Genocide is not just an Armenian problem, but more an international issue which still needs to be addressed by the international community.

Hovannisian is quite clear that the injustices of one nation against any another requires retribution and that Armenian advocacy now needs to be more articulate and that there is a moral imperative to go beyond mere semantics.

Commenting on the problems and prospects, 60 years after the UN Genocide Convention, Dr. William A. Schabas, a legal scholar and Director of the Irish Centre for Human Rights at the University of Ireland, put the issue in perspective: International law is not generally concerned with ?crime? as it is generally understood, but genocide is now (since the 1990?s) recognised as an inter- national crime.

In fact, as an American lawyer, writer and historian Alfred de Zayas, argued ?because of the nature of the crimes, State responsibility for reparation to victims and descendants and individual criminal liability are not subject to prescription or any statutes of limitation.?

Alfred de Zayas, who is currently a professor of international law at the Geneva School of Diplomacy and International Relations, buttressed his argument by saying: ?In the case of the Ottoman genocide against the Armenians and other Christian minorities, during and after World War I, the perpetrators are dead and beyond the reach of criminal justice. But the Turkish State remains liable for the crimes and the Genocide Convention of 1948 can be applied retroactively as there are numerous legal precedents for such a process.? In his view, ?there is not only a legal but also a moral obligation on the part of the international community to take appropriate action in order to ensure that a measure of justice is achieved in respect of all victims of genocide and their descendants.?

But irrespective of these changed perceptions, there is little doubt that while the principles of restorative justice might encourage a sense of ?positivism? amongst the Armenian community, what is now required is political willingness and action to address this issue. And, to begin with, that means an unconditional acknowledgement of what happened in the past, followed by establishing a symbolic compensation fund and the restitution of cultural property etc.

Finally, an official Turkish apology ?in a spirit of reconciliation,? would help heal the insufferable memories of a traumatic historical experience.

After all, according to Prof. Alfred de Zayas, it is worth remembering in this context that several great nations have recognised mistakes committed by prior governments in the past, and have issued formal apologies to the victims and their survivors, including Germany, Austria, Canada and more recently the United States and Australia.

Incidentally, in 2005, the International Association of Genocide Scholars confirmed, there had been a ?systematic genocide? of Armenian citizens between 1915 and 1923 – which has been consistently denied by the Republic of Turkey, which succeeded the Ottoman Empire, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

But, reassuringly, countries like France, Argentina, Greece and Russia, where the survivors of the Armenian Genocide and their descendants live, have recognised the Armenian Genocide although Turkey continues to dismiss the evidence about the atrocities as mere allegations. However, to date, 21 countries have officially recognised the events of the period as genocide – the first of its kind in modern times.

What is now most required is some adequately sensitive gesture of reconciliation. At least that is what the organisers and participants of the conference (and many others) still dare hope for. Whether or not the response of the international community in general and the Republic of Turkey in particular matches their aspirations, still remains to be seen. But what is not acceptable is indifference to a crime as brutal as genocide – any genocide.

Anand Sagar is Khaleej Times? Foreign Editor, Professor Emeritus of the Indian Institute of Journalism & New Media, Bangalore, and Former Visiting Fellow, University of Oxford. He can be reached at [email protected]