Interview with the author Avedis Hadjian

Interview with the author Avedis Hadjian

For Azad-Hye

What was your main stimulus of writing this book?

I am not sure I can pin down a single reason for writing it. Yet, if I had to narrow it down to one major factor, I would probably say that my drive was a yearning — powerful, as it was — to see if there were still Armenians left in the geography of the Genocide, in the historical lands of Armenia that make up most of what now is Eastern Turkey. But there were so many things that piqued my curiosity: the mystery that surrounded the Hamshentsis, a minority of Armenian origin that, in Turkey, has been converted to Islam approximately since the 16th century; the intriguing references to secret Armenians in the mountains of Sasun. So, at some point I decided to leave it all — work, New York, everything— and go and see for myself.

What did you discover for yourself during writing this book and what you expect others to discover while reading it?

I discovered how complex the hidden Armenians are as a group, if you can call it so, and, by extension, how nuanced identities can be. I am still astonished at how simplistic my views were when I set out to meet the Armenians who stayed on the ancient homeland. As for the readers, I would generally be cautious about nudging them in one sense or another, yet I would hope to have conveyed in all its subtlety how identity of any kind —national, religious, personal— is a variable quality, more for some than for others.

Why Turkey does not accept Armenian Genocide and what can be the goad for Turkey to do it?

It would be probably fair to say that there is an intertwined set of reasons why Turkey does not recognize the Genocide. Probably a major reason is that the Genocide was foundational for Turkey (and, this the Kurds should remember as well, also for the lands they now call Kurdistan, which overlap with Western Armenia). Then there is the issue of reparations, which can be intractable given the scale of the events discussed here and the implications, which in all fairness would or should include in theory a redrawing of the maps and international borders. Let us leave aside for a moment whether that is realistic or not. It is a theoretical possibility, enough to intensify paranoia in a country like Turkey where —in the absence of reliable information— conspiracy theories are common currency. Any Armenian who is minimally involved in the affairs of his community knows the challenges faced by Diaspora institutions —charities, schools, the Church and the churches— and yet in Turkey it is not uncommon to read about Armenian-Greek cabals plotting to break up the country. And you don’t hear this only from Turkish nationalists; even Besse Hozat, a high-ranking militant in the PKK, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, a guerrilla group that is relatively supportive of Armenians, five years ago made comments to the press saying that “Greek and Armenian parallel states in Turkey” were preventing the country’s democratization. She took it back after a massive outcry, but the fact she said it is indicative of a pattern of thought. Parallel states! There are even fewer Greeks than Armenians left in Istanbul, let alone in Turkey. As for Armenians, so many of them do countless sacrifices to keep churches and schools running. And yet there are people in Turkey who seriously believe that gibberish: that Greeks and Armenians are conspiring to take over the country.

I do not see what would goad Turkey towards recognizing the Genocide. For a while I thought it was a matter of time before they did, but I am no longer convinced about it. Perhaps a settlement of reparation claims could open the Turkish state towards recognizing the Genocide, but I very much doubt it. The geopolitical changes required for such a move would be so radical and dramatic, as I see it now —and certainly I may be wrong— that speculating about it is not worth it.

Is it possible that Armenia and Turkey can come to a common denominator one day and if yes, then how?

This question brings me back to my previous mention of major geopolitical changes. It might happen: an enlarged European Union? A new regional, overarching alliance? That, however, would imply a major geopolitical reset, overturning some fundamental tenets that have held for more than a century. The emergence of an independent Kurdistan might be one such major game-changer. Yet the ramifications of such an event could be unpredictable for all countries in the region including, obviously, Armenia and Turkey.

Once you mentioned that “Turkey is a state which still hostile attitude towards not only Armenia, but also all Armenians”. The question is-Do you think that the denial of the Armenian genocide is only Turkish governmental position or also Turkish people?

That question is too broad. Yes, it is certainly the position of the Turkish state. I would venture that even if one day Turkey came to be led by a politician who does recognize the Armenian Genocide, I would still doubt that the Turkish state would shift over this. In other words, it would still be Turkey’s position that it was not a Genocide and, at most, the issue would boil down to semantics which, ad extremis, would amount to nonsense. I do know Turkish government officials who, privately, acknowledge the Genocide. There is one version, of unconfirmed source, that former Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu privately calls the Armenian Genocide by its name. Now, I do not know that, but regardless of one’s own convictions and views, I do find it hard to believe that well-read Turkish officials would not be embarrassed to deny what is a historical fact. That does not necessarily make them good people. Some of the architects of the Armenian Genocide were well-spoken too. But if recognition is going to happen, these will be the officials the Armenian side will have to engage.

As for the people, of course there are many Turks who know of the Genocide and feel bad about it, and will openly say so. There are also obviously those who do not recognize it, which is a way of acknowledging it too. For those nationalist Turks that deny its veracity, it is a way of justifying their hatred of Armenians, which in Turkey you can still express openly and, up to a point, with impunity.

What significant changes did Hrant Dink’s murder bring in Turkish society?

Again, it awoke a part of Turkish society to this elephant in the room that they were told by the government to ignore. There is definitely a before and after Hrant Dink’s murder in the dynamics of Turkish-Armenian perceptions, if not so much in the relations. As much as there are Turks in favor of a more equal and democratic society, there are those —possibly a majority— that have a more conservative outlook and who, indeed, just voted for the re-election of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan as president.

What should our attitude towards Islamized Armenians be and what was their attitude towards Armenia and Armenians?

I do not favor collective attitudes towards one group or the other. I would say that the islamicized Armenians have been defying all odds to survive as Armenians in a very hostile environment and that they know better than those Armenians outside of Turkey what they should do. As for their attitudes towards Armenia and Armenians, they are as varied as these families are: some are still in touch with their Christian relatives in Istanbul, Armenia or the Diaspora; some acknowledge an Armenian origin but feel that their Islamic identity trumps that; others are descendants of islamicized Armenians but are atheists and feel close to the Armenian Church. It is truly very nuanced, like a very ornate rug, richly colored with many threads.

About the author:

About the author:

Avedis Hadjian has travelled to the towns and villages once densely populated by Armenians, recording stories of survival and discovery from those who remain in a region that is deemed unsafe for the people who once lived there.

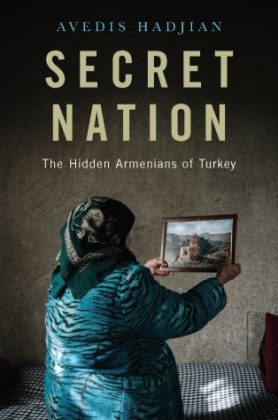

This book takes the reader to the heart of these hidden communities for the first time, unearthing their unique heritage and identity.

Revealing the lives of peoples that have been trapped in a history of denial for more than a century, Secret Nation is essential reading for anyone with an interest in the aftermath of the Armenian Genocide in the very places where the events occurred.

About the book:

It has long been assumed that no Armenian presence remained in eastern Turkey after the 1915 Genocide. In recent years, a growing number of “secret Armenians” have begun to emerge from the shadows. Spurred by the bold voices of journalists like Hrant Dink, the Armenian newspaper editor murdered in Istanbul in 2007, the pull towards freedom of speech and soul-searching are taking hold across the region.

Hardcover: 624 pages

Publisher: I. B. Tauris (June 30, 2018)

Language: English

ISBN-10: 178831199X

ISBN-13: 978-1788311991

Dimensions: 6.5 x 2 x 9.3 inches

Interviewed by Ani Dallakyan

Coordinated by Hrach Kalsahakian