By Luke Baker

By Luke Baker

Behind the door of 36 al-Khanka Street, a steep, stone alleyway squeezed between the Christian and Muslim quarters of

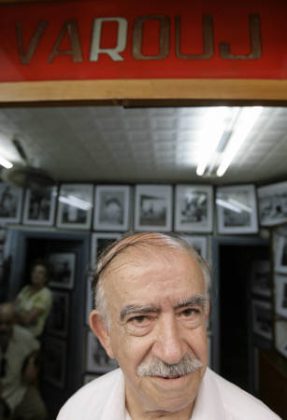

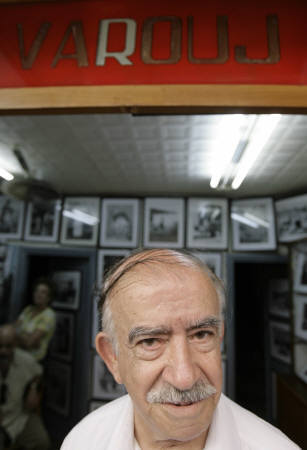

Varouj Ishkhanian's photographic studio is lined with emotive images from the last 130 years, tracing

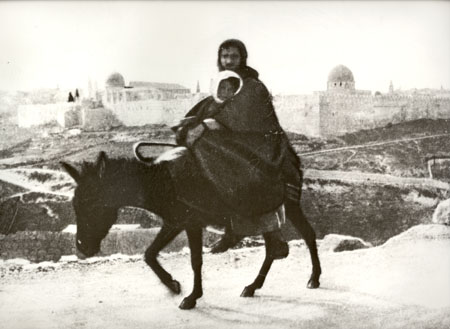

From wizened Ashkenazi Jews studying the Torah in the early 1900s, to camel trains leaving Damascus Gate on their way to

“Every picture contains more than one thousand words,” the 73-year-old Ishkhanian says with a chuckle, flicking through a stack of thick, time-worn albums of original photographs piled on his desk, each image indexed and dated.

“This one was taken by my grandfather, one of the first that he took,” he says, pointing to a faded brown-and-white picture of Jewish women praying at the Western Wall in the late 1800s.

There are portraits too of bare-breasted gypsy women during Ottoman rule, of the execution of a crook by the Ottoman authorities in 1905, and of Arab fishermen on the

An Armenian who was born and grew up in the

ROYAL MANDATE

He started taking pictures in his teens, in the mid-1940s, when he would help out his grandfather Kirkor at his photographic shop on

During the 1948 war that followed

Having developed a knack for both news and more lucrative wedding photography — his collection contains several portraits of Arab girls preparing for marriage — he cajoled the Jordanian authorities who then administered

“I was working for several newspapers at the time and I just kept pushing and pushing and eventually they said okay,” he recalls. “Very soon I was going to

He used to have a signed portrait of Hussein, who died in 1999, in pride of place in the window of his studio, but took it down in 1967 after the Israelis captured the West Bank and East Jerusalem from

Now a signed portrait of Hussein's son, King Abdullah, hangs inside the small shop instead, overlooking Ishkhanian's desk. A portrait of Ishkhanian himself, looking dapper in his late 20s, hangs from the same wall, just above that of Abdullah.

Other images include pictures of his father, Sarkis, who was never bitten by the photography bug, instead working for the British authorities during their mandate of

EYE ON THE PAST

As well as capturing many moments in

A picture from the early 1900s shows Jewish men and women praying together at the Western Wall, the most sacred site in Judaism, whereas now they pray in separate sections.

Another from the same period shows houses very close to the Wall that Ishkhanian said once belonged to Moroccan Arabs, whereas now the area in front of the Wall is an open square.

Another from the same period shows houses very close to the Wall that Ishkhanian said once belonged to Moroccan Arabs, whereas now the area in front of the Wall is an open square.

However, he refuses to be drawn into any political discussion that his photos might throw up, leaving them to speak for themselves. “The pictures show everything,” he says firmly.

With his sight gone in one eye after so many years in a dark room, Ishkhanian now spends his days in his studio selling prints of the collection for 50 shekels (about $11) a piece. His son Sarko helps out and still takes pictures.

He also helps prod Ishkhanian's sometimes patchy memory, reminding him of what year he got married and when his three children were born. But the father remembers clearly when he opened his studio — it was 1964.

“It was after I worked for the king, when I had some money. Then, we weren't thinking about the future, it was all dancing and parties,” he says with a smile. “It was before I got married, before the problems of 1967. It was a good time.”

Showing off his favourite photograph — a view he took in 1952 through the window of the Dominus Flevit church, looking towards the Dome of the Rock and the Western Wall — he laments how business has declined over the past six years, since a Palestinian uprising erupted.

But he remains buoyant and enthusiastic. “Every day is good,” he says. “I still look at everything, and I still take pictures, even if not as well as before.”

Source: “Reuters” from

|  |

Photo 2: Varouj in his laboratory

?

Photo 2 and 3: Samples of photos