Kevorkian: “I'm not going to do it again”.

Kevorkian: “I'm not going to do it again”.

He says he'll follow the law and be an advocate

By Kathleen Gray

A compassionate doctor to some, a ghoulish murderer to others, Jack Kevorkian will, in less than six months, become something he hasn't been for more than eight years — a free man.

Kevorkian, a frail 78-year-old, was granted parole Wednesday by two members of the Michigan Parole Board after he promised not to conduct any more assisted suicides. He will be eligible for release June 1.

Oakland County Prosecutor David Gorcyca said he would not appeal.

“He has served his minimum term, and I did not object to his release,” Gorcyca said. “I'm certainly not particularly surprised, just due to his alleged health concerns.”

Known as the assisted-suicide doctor and Dr. Death, Kevorkian claimed to have helped at least 130 terminally or chronically ill people die during the 1990s, though he told parole board chairman John Rubitschun that he turned down six or seven prospective patients for every one he helped.

He told Rubitschun he would push for the legalization of assisted suicide after his release, but promised to not participate in any form of assisted suicide or euthanasia.

“You can put any conditions you want on me. I'm not going to do it again,” Kevorkian said in a Dec. 7 hearing, according to an account based on notes from the meeting. “Anything that will bring me back to prison, I will avoid. Prison is not a place a live.”

Kevorkian was convicted in 1999 of second-degree murder in the Sept. 17, 1998, death of Thomas Youk, 52, of

The death was different from others in two ways. First, it was videotaped and aired on the CBS show “60 Minutes.” Second, Youk was unable to press the button to deliver a fatal dose of drugs, and the tape showed Kevorkian doing it for him, which provided prosecutors with evidence that Kevorkian had stepped past the assisted-suicide line.

Kevorkian's defiant approach brought physician-assisted suicide to the national spotlight. In 1998, an

Kevorkian said he should have gone the legal route to advocate for assisted suicide.

“If I had to do it again, I would have done it that way,” he said.

Although Kevorkian won't be eligible for release until June 1, his attorney, Mayer Morganroth, said he'll once again ask Gov. Jennifer Granholm to release his client early from the Lakeland Correctional Facility in Coldwater. The governor has denied requests to commute the sentence four times.

“Certainly, it's a relief; it's a man's life we're talking about,” Morganroth said. “The next thing we have to do is talk to the governor so he doesn't die in prison in the next six months.”

According to Morganroth, Kevorkian suffers from hepatitis C and high blood pressure. He takes insulin four times a day and has hardening of the arteries. He recently fell, breaking two ribs and his wrist.

Ruth and Sarah Holmes, a mother and daughter who have become friends with and frequent visitors of Kevorkian, said he can't wait to get home for a turkey wrap, some pickled vegetables and some fresh fruit.

“He was very grateful that the process finally worked,” said Ruth Holmes of Bloomfield Hills, after talking to Kevorkian on Wednesday. “He was not in great shape when he went in, and he's had a rough winter.”

Sarah Holmes attended the parole hearing and told Rubitschun that few people know the side of Kevorkian that she has seen — the musician, the poet, the painter, the historian, the family man.

“I tried to add the human element of Jack Kevorkian,” she said. “He is the most honest man you would ever meet, when he gives his word, he sticks with it.”

But retired Waterford Police Chief John Dean said he would oppose Kevorkian's parole.

“I'm convinced he'll do it again to make a statement,” he said.

Kevorkian's first assisted suicide was in June 1990, when Janet Adkins, a

The state revoked his medical license in 1991 after he had conducted five assisted suicides. Without a license, he could no longer buy some of the drugs he used, so he began using different techniques, which included the use of carbon monoxide canisters.

He was acquitted of murder three times and got a mistrial declared in a fourth case.

“He was, at the time he went to prison, perhaps one of the most famous people in the world,” Fieger said Wednesday.

“Certainly, he moved the issue of individuals' rights not to suffer at the end of lives, far greater than any person before him.”

Kathleen Gray's e-mail: [email protected].

Detroit Free Press staff writer John Wisely and the Associated Press contributed to this report.

[Article adjusted for our readers]

HOW LIVES WERE ENDED (By Ruby Bailey)

With $45 worth of materials in the 1980s, Dr. Jack Kevorkian created what he called a suicide machine — a simple, effective device for assisting people who wanted to end their lives.

The contraption was made of three bottles: One contained saline solution, one held a sedative, and the last had lethal potassium chloride.

Kevorkian hooked people to the device and allowed them to press a button, starting the intravenous flow from the bottles.

In 1991, after his medical license was revoked, he switched to a canister filled with carbon monoxide because he was no longer able to get potassium chloride.

PROFILE OF JACK KEVORKIAN

Age: 78

Claim to fame: Says he helped more than 130 people with various illnesses end their lives.

Nickname: Dr. Death.

Personal: Son of Armenian immigrants, raised in

Education: Graduated from the

Employment: Worked at Pontiac General, Detroit Receiving and several

Hobbies: Music, painting, languages, poetry. Published a book, “Glimericks,” while in prison.

– In the heyday of his assisted-suicide practice, Dr. Jack Kevorkian's name became part of the US popular culture.

– A popular paint pattern for fishing spoons used for salmon and trout is called Kevorkian because it lures the fish to their deaths.

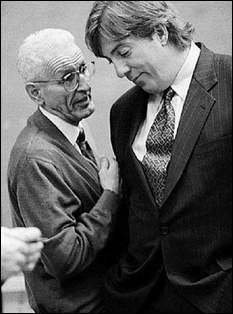

Photo: Kevorkian talks with his attorney, Geoffrey Fieger, at trial. (February 1996 photo by CHARLES V. TINES/AP)

Source:

http://www.freep.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20061214/NEWS06/612140349/1001/NEWS